Exponential Idle Basics

Feel free to use the glossary or basics as needed.

This intro and following guide are designed to help you play through the 1 to ee2000

section of the game. This introduction will give you some fundamentals to help you progress

while playing this section of the game.

If you don’t want to have spoilers for the later game, don’t read

further ahead than you are already.

Variables and Upgrades #

Variables are the main purchases in the game. They will be the most important to buy, and you should buy them as priority because they increase Lifetime f(t) faster. All of the variables purchasable are below. You will not be able to get all of them right away but will be able to get them all as you keep playing. This screen is found by pressing the <Upgrades> button between the upgrades and the main equation graph.

Upgrades are where additional boosts to variables lie. They are crucial to progress and should be bought often. You will be able to see items that can be purchased with f(t),

Variable Names and Uses #

Class: breakdown;

last_row: false;

| Variable Names | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [class=“bheader”;]x | x | [class=“bheader”;] |

gamma | [class=“bheader”;] |

nu |

| [class=“bheader”;]y | y | [class=“bheader”;] |

delta | [class=“bheader”;] |

xi |

| [class=“bheader”;]z | z | [class=“bheader”;] |

epsilon | [class=“bheader”;] |

mu |

| [class=“bheader”;]s | s | [class=“bheader”;] |

zeta | [class=“bheader”;] |

psi |

| [class=“bheader”;]u | u | [class=“bheader”;] |

eta | [class=“bheader”;] |

sigma |

| [class=“bheader”;]v | v | [class=“bheader”;] |

theta | [class=“bheader”;] |

phi |

| [class=“bheader”;]w | w | [class=“bheader”;] |

iota | [class=“bheader”;] |

tau |

| [class=“bheader”;] |

alpha | [class=“bheader”;] |

kappa | [class=“bheader”;] |

rho |

| [class=“bheader”;] |

beta | [class=“bheader”;] |

lambda | [class=“bheader”;] |

t |

Class: breakdown;

last_row: false;

| Variable Uses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [class=“bheader”;]x | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var |

| [class=“bheader”;]y | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var |

| [class=“bheader”;]z | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

prestiges |

| [class=“bheader”;]s | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

supremacies |

| [class=“bheader”;]u | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

graduations |

| [class=“bheader”;]v | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

graduations |

| [class=“bheader”;]w | main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

theories |

| [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

theories |

| [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

main var | [class=“bheader”;] |

time |

What does ee mean? #

You start out with normal numbers and quickly work your way up to

Achievements and Minigames #

- Achievements are just that. They are goals to reach that give you stars as reward.

- Minigames are puzzles that you can solve that will give you stars as a reward for solving them. Check out the Minigame Guide for how to solve each puzzle and more resources.

Stars and Star upgrades #

- Stars are a currency that operates outside of the main game that you use to purchase star upgrades.

These upgrades range from QoL (Quality of Life) features to boosts to the gameplay. For the most part, you should

prioritize new variables as soon as you can, EXCEPT for Autoprestige. Autoprestige is a huge

boost in progress due to impossible to replicate levels of optimization, and you should prioritize it over variables of a similar cost. More details on

star upgrades to prioritize can be found in following guides.

Autoprestige expression #

Autoprestige expression #

timer(pt * d(ln(ln(db / b + 1))) < 1)

> 3 * tr && db > b

Autoprestige explanation #

The idea behind

The general idea of a good expression would be to “maximize

We could divide the ratio by time, but that doesn’t make sense because ratios are applied multiplicatively (e.g. ratio

Therefore, we get the expression

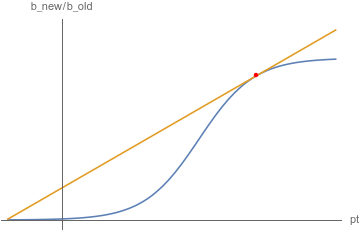

Visual representation #

Autosupremacy expression #

Autosupremacy expression #

dpsi + psi > min(costUpS(1),

costUpS(2), costUpS(3))

&& (((lf < ee48000)

&& ((log10(log10(gf)) >=

log10(log10(lf))-400)

|| ((log10(log10(gf)) >=

log10(log10(lf)) * 0.8)

&& (((dpsi + psi > costUpS(1, 3))

|| (dpsi + psi >

(costUpS(2) + costUpS(1, 2))))

|| ((log10(log10(gf)) >=

log10(log10(lf))-10000)

&& (dpsi + psi > costUpS(3, 3)))

|| ((log10(log10(gf)) >=

log10(log10(lf))-4000)

&& (dpsi + psi > costUpS(3, 2)))

|| ((log10(log10(gf)) >=

log10(log10(lf))-1000)

&& (dpsi + psi > costUpS(3, 1)))))

|| ((log10(log10(gf)) <

log10(log10(lf)) * 0.8)

&& (timer(d(ln(db / b + 1) / pt) < 0)

> 3 * tr && db > b

&& dpsi + psi > min(costUpS(1),

costUpS(2), costUpS(3))

&& ln(1 + max(1, log10(sf)) /

smooth(max(1, log10(gf)),

(st > tr) * ee99)) /

max(1, st) <

smooth(ln(1 + max(1, log10(sf)) /

smooth(max(1, log10(gf)),

(st > tr) * ee99)) /

max(1, st), (pt > tr) * ee99)))))

|| ((lf >= ee48000)

&& (((lf < ee52000)

&& ((costUpS(3) < e411

&& psi + dpsi > e411)

|| (costUpS(3) < e531

&& psi + dpsi > e531)

|| (costUpS(3) < e551

&& psi + dpsi > e551)))

|| ((lf < ee58000)

&& (costUpS(3) < e511

&& psi + dpsi > e511))))

|| ((lf < ee75000)

&& (costUpS(3) < e571

&& psi + dpsi > e571))

|| (costUpS(1) < e52

&& psi + dpsi > 4.2e51))

Do a manual supremacy when you input this expression and never enter the

edit expression field again afterwards. Make sure autobuyers are on x1

or xMax.

Reference Locking Smooth()

Reference True /False auto expression evaluation

Autosupremacy explanation #

The autosupremacy expression is an attempt to do the autoprestige expression, but for supremacy. It tracks the same information, but over multiple prestiges. It is harder to make an autosupremacy expression than an autoprestige expression because after a new prestige, Supremacy

Smooth() for auto expressions #

Internally, smooth is implemented using an exponential moving average. Here are some ways to use this construction.

Method 1: Moving average #

If a value fluctuates too much, you can use smooth so that the value does not go rampant, triggering some conditions incorrectly. One main example is to use it when you use multiple

For instance,

Method 2: Lock #

Due to the nature of the expression, if the second input of smooth is very large, then there will be no average at all: instead of taking a normal average, we can skew the weights so that any new value is too small to be noticed. As a very simple example, we can calculate averages like

A simple expression like

However, we can do better: instead of simply locking values, we can control when the locking mechanism comes in. Using conditions, we can switch back and forth between indefinite locks and instantaneous updates:

Method 3: Cumulative maximum #

If we have two really large values, the average of the two will be in favor of the larger of the two. In fact, if the two numbers are really really big, the average will be indistinguishable from the larger of the two due to finite data storage (term: floating point precision). We can abuse this idea to convert the input of smooth into a very large value, thereby converting averages like

For example,

Reference formula #

True /False auto expression evaluation #

If you enter the autoprestige or autosupremacy field to enter the expression, you will most often notice it evaluate as